We first heard of Emilio through the Mezcalero brand. Throughout the 2010s, the Mezcalero brand was known for bringing new producers, agaves, and distillation methods to the US market. It’s something they still do today, and they were the first brand to bring Emilio’s mezcal to the US in 2015, as single batch named Mezcalero No. 12. I distinctly recall that our friend Philipp (now of Heavy Metl Imports), who at the time was working at the Austin Wine Merchant, stashed a few bottles of Emilio’s Mezcalero No. 12 in a case of wine for us. There were dozens of wine cases stacked up against the front window of the storeroom, and Philipp lifted two or three cases off the top to get to the bottles he’d hidden for Tyler and me. The bottle was $67 back then (wow, how times have changed!). Upon first taste, Emilio’s Cupreata was immediately something that we wanted to find more of, but it was almost impossible to find anyone who could point out Michoacán on a map, let alone provide much information about Emilio.

Siembra Spirits, Certification, and Tequila

It wasn’t until we met David Suro shortly thereafter when we really began to understand Emilio and his importance to the community in which he produced, as well as the Michoacán traditions that he represented. For those living under a rock, David Suro has been an icon in the agave spirits community since the 1980s when he opened the now famed Tequilas Restaurant in Philadelphia. Upon opening the restaurant, he was immediately confronted with a grave issue: all of the tequila available in the northeast (and most of the US for that matter) was terrible by today’s standards. To fix this, he founded Siembra Spirits and Suro Imports, an import company to bring quality tequila and agave spirits to the US market. That was revolutionary at the time, and he continues to push the envelop of agave spirits. He recently published a book, with co-author and ethnobotanist Gary Paul Nabhan, Agave Spirits : The Past, Present, and Future of Mezcals, which is a testament to his lifelong dedication.

After working with some of the finest tequila producers for several decades, David expanded his import portfolio to include a single mezcal producer: Emilio Vieyra. It speaks volumes about Emilio that David, with all of his in-depth knowledge and experience in agave spirits, chose a relatively unknown producer (in the US at least) from Michoacán to represent the mezcal category in the Siembra Spirits portfolio. We originally met David at an impromptu tasting in the back room of the Austin Wine Merchant (again with our friend Philipp) in 2017. David walked us through his agave line up, which by then included both tequila and Emilio’s mezcal, which was bottled under a new brand called Siembra Metl.

During that tasting, David gave us a much fuller picture of the man behind the mezcal. We learned that Emilio was the leading vocal advocate to have Michoacán included in the mezcal Denomination of Origen, which allowed for agave spirits producers in the state of Michoacán to legally call their spirits mezcal. Following this decision by the Consejo Regulador del Mezcal (CRM), Emilio became the first mezcalero to be certified by the CRM in the entire state of Michoacán. By doing this, he lead the way for more producers in Michoacán to become certified and thus gain access to larger markets to sell their mezcal, both in Mexico and internationally. This was a dream for both Emilio and his father, who lived to see this happen. The El Legado batch from Don Mateo is a tribute to this certification and Emilio’s father, Don Jose Emilio Rangel. This mezcal is the first batch to have ever been certified in the state of Michoacán.

David also explained how Emilio was working with Cascahuin Tequila to create the Cascahuin Ancestral Tequila, which had yet to be released at that time. They’ve released several incredible batches now, as it is a tequila produced using traditional mezcal processes in the state of Jalisco. Emilio is critical to this project as he has the ancestral skill and knowledge of the traditional mezcal production processes, including the use of the Filipino still. You can read more about that project here in our blog Cascahuín & Ancestral Tequila.

The area built for Siembra Ancestral production at the Cascahuin tequila distillery in Jalisco. Notice the pit oven for cooking agave and the shallow cement pit to the right, which is used for hand-milling the agave after they are cooked.

The Filipino still used to produce Siembra Ancestral, very similar to the Filipino still used at Emilio’s vinata.

Siembra Metl vs Don Mateo

Emilio’s first few batches that came into the US via Suro Imports were under a new brand named Siembra Metl. David explained to us that this was a way to introduce Emilio’s mezcal to the market under a similar label to his Siembra Valles and Siembra Azul tequilas that were already well-renowned. Under the Siembra Metl label, Emilio’s name and reputation were quickly solidified, and Emilio’s family brand, Don Mateo de la Sierra, was imported directly by Suro Imports thereafter. The Don Mateo de la Sierra brand is significant as it’s named after Emilio’s grandfather, who was known as Don Mateo.

The original import of Emilio’s mezcal via the brand Siembra Metl (right) quickly led to the import of Emilio’s family brand Don Mateo de la Sierra (left).

Arriving at the Vinata

As we planned our trip to Michoacan in early 2023, David shared Emilio’s phone number with me. I texted him via WhatsApp and he almost immediately responded, inviting us to his vinata (distillery) on the last day of our trip as he’d be distilling Cenizo that day. He suggested that we get in touch with someone named Alva, who lives in Morelia, the capital city of Michoacán. She helps Emilio with the paperwork associated with certifying his mezcal and she knows how to get out to his vinata. She arranged to have a driver pick us up at our AirBnB near the main cathedral in Morelia. The driver took us out to a Barbacoa stand about 30 minutes from the city center. This was the final day of our trip, and we’d been visiting vinatas nonstop for five straight days at that point. We were glad to grab some breakfast Barbacoa and get our legs back beneath us. Alva met us there. We bought some beer at a nearby Oxxo and then headed out to Emilio’s vinata.

Driving out to the vinata in San Miguel is reminiscent of driving through a pine forest in high-altitude Colorado. It’s interesting because I’ve often thought that Emilio’s mezcal, regardless of the agave he uses, has a piney flavor to it. Little did I know that his vinata is located in the middle of a pine forest on the steep slopes of a mountainous canyon. You enter his property though a large metal gate. Then you drive about 2-3 minutes on a loosely packed gravel road. Then you go through another metal gate and descend into the canyon. The drive was too steep for our van so we parked near the house that Emilio is building for his mother. We walked the remainder of the way down through the pine-lined road to the vinata on the side of the mountain.

We were first greeted by Emilio’s dog Cookie. She’s an old mutt-looking dog that kind of resembles some sort of golden retriever mix. She barked at us as we approached as if to tell us that she was the guardian at the gates. That tough exterior didn’t last long though, as she could hardly contain her excitement for visitors. She began quickly wagging her tail as we drew closer, eventually rolling over on her back to ask for a belly rub. Little did we know at the time, but this first interaction with Cookie would foreshadow our entire experience for the remainder of the day.

Emilio met us at the underground pit oven as we approached. He smiled and you could tell that he was very excited to have visitors. I shook his hand to greet him. His hand was so tough and hardened that it ripped open one of the blood blisters that my hands had accumulated harvesting an agave a few days earlier. I pushed the freshly bleeding cut into my shirt and tried to act as if all was good and normal. Emilio smiled with the same sort of soft, friendly personality that Cookie had just shown us moments before.

One of the first things he told us was that he employs as many people as possible from the nearby town, giving them jobs so that they don’t need to go to the US to find work. This was clearly a point of pride for him and something he prioritized. In this way, it was evident from the beginning that Emilio was doing this for a lot more than just himself. Indeed, Don Mateo is a community project that he is leading.

The loaded oven at the Don Mateo vinata.

A view of the vinata from the oven. You can see the agave fermentation pits and the Filipino stills in the background.

The Man, The Myth, The Legend

Emilio’s father, who was born and raised in Michoacán, worked for about 10 years between California and Texas, working for wine producers and other agricultural practices. He returned to Michoacán to marry the love of his life, Doña Delia. They were married in Michoacán but quickly returned to Texas for work. Emilio was born soon after in Houston, Texas and he lived there for 2 years before his parents moved back to Michoacán for good. Emilio has US citizenship as well as Mexican citizenship, a fact that causes many of his employees around the vinata to joking call him gringo, despite having lived all but two years of his life in Michoacán.

His father produced mezcal and taught Emilio everything he knows about agave, spirits production, family, community, and just about anything else one would need to know. Thanks to his father, Emilio is a 6th generation mezcalero, with over 400 years of mezcal production in his family. This is something that Emilio takes very seriously and he is quick to honor his father, who sadly passed away in September of 2018. It’s clear that Emilio’s father was the world to him, and a leader in the community.

The Woman, The Myth, The Legend

Before we visited, we spoke to a lot of people in the US and Mexico about our trip to visit Michoacán. Whenever we mentioned Emilio and our plans to visit him, everyone raved about his mother, Doña Delia. You’ve likely heard the saying behind every great man, there’s a great woman. In this case, it’s Emilio’s mother. Everyone with whom we spoke about visiting Emilio mentioned his mother. Many mentioned her incredible food (which we got to taste first hand… it’s even better than legend will tell), others mentioned her kind demeanor, and still others told of her mezcal pechuga recipe.

The Don Mateo pechuga, which many in the US have grown to love, is typically made with maguey Cenizo or Cupreata. Emilio makes the first two distillations of the mezcal, and then it’s Doña Delia’s unique recipe that is added to the third distillation. This recipe includes meats like iguana, deer, or turkey. It also includes a unique blend of herbs and spices that only Doña Delia knows how to properly prepare. Emilio told us that the pechuga is the top seller in the US. Go out and get a bottle!!

The Vinata and Filipino Stills

The vinata itself is just 3 years old. Prior to this vinata, they rented space for production at a community vinata nearby. They have the new vinata all to themselves, and it’s in the perfect location. There is a fresh water spring just above the mezcal production area on the mountainside. The spring water is channeled through the vinata via a series of aquaducts, providing water for the fermentation pits as well as continuous cool water running over the condensation plates in the stills. In addition to aiding in the mezcal production process, the spring water then travels further down the mountainside to the agave nursery that sits just below the vinata on the hill, providing fresh clean water to irrigate the agaves as they grow before being re-planted in the fields. The agave nursey is run by his mother, Doña Delia. It’s an impressive nursery of Cupreata that clearly shows her passion and dedication to the plants and environment around her.

One of Emilio’s Filipino stills.

Emilio only produces 2-3 batches of mezcal per month, which is largely by choice, based on the amount of agave that is mature. He also produces some rum, but the fermentation for each plant (agave and sugar cane) is done in separate containers. He ferments his rum in above ground wooden tanks, and he ferments his agave in underground cement pits that are lined with wood. He separates the rum and mezcal fermentation areas as he says that the rum puts flavors into the wooden tanks that he does not want in his mezcal. We’ve visited other maestros who use the same fermentation tanks for both sugar cane and agave. It does make a difference, and we were glad to see that Emilio takes the care and has the attention to detail to separate the two. For the agave fermentation, we’ve seen underground pits in the past, but typically the fermentation pit is lined by either cement or stone. In this case, Emilio has a layer of wood lining the interior of the agave distillation pits. He says this helps with fermentation, likely capturing some yeast in the wood grain from batch to batch.

The in-ground agave fermentation pits. Notice that they are lined with wood, likely capturing some yeast cultures and other bacteria from batch to batch.

The rum fermentation tanks, set aside from the agave fermentation. Emilio does not want the flavors of the rum to impact his mezcal.

The agave nursery at the vinata. This is maintained by Emilio’s mother, Doña Delia.

He says about 80% of the agaves he uses are grown in his own fields, with the remaining 20% being purchased from the nearby community in order to meet the demand for his mezcal. This not only helps him produce a larger amount, but it helps support the community. Emilio walked us over to the Filipino stills and told us that they were the largest ancestral Filipino stills in all of Michoacán. There was 60% ABV Flor de Cenizo flowing from the still. The term flor in Michoacán is similar to puntas in other areas of Mexico like Oaxaca. It’s the first cut from the still and it contains the highest concentration of alcohol. Additionally, Emilio intentionally distills very slowly, which he learned to do from his father. For him, this achieves the best results. He says it takes him 36 hours to distill a single batch (not including all the other aspects of production, like agave cooking, milling, fermentation, etc… which take weeks in total).

Emilio showing us the perlas in the flor to demonstrate the high alcohol content in the first cut from the still.

His Father's Truck

Emilio wanted to show us some of his agave fields. He also had a group of workers who were out at his agave field in El Limon that he needed to pick up that day. They had been working in the nursery and fields there for 2 straight days, staying in a small cabin onsite. Emilio told us it would be about a 1.5 hr drive to the fields. Before we left the vinata Emilio explained that he wanted to take us in his father’s old truck. He had a newer truck, which we could see there at the vinata, but it was important to Emilio to keep his father’s truck functioning as a part of the vinata’s day-to-day operations. Tyler and Alva climbed into the cab with Emilio, and I jumped into the back bed of the truck.

The truck that belonged to Emilio’s father, something that he takes great pride in.

We made it about 20 minutes down the road before Emilio noticed a problem with the truck. It seemed to be something wrong with the front axel. Unfortunately my Spanish vocabulary with car parts is pretty low. Las cosas could only get me so far, so I didn’t get all of the details, but understood the main premise. We stopped by the side of the road for about 30 minutes. The landscape around us was incredible: pine forests with views out to mountains and open greenspace all around. Emilio worked under the truck and we tried to be useful, but eventually he had to call back to the vinata for help. Two workers from the vinata arrived in Emilio’s newer truck. They had some additional tools and we were back up and running for about 30 seconds before Emilio threw his hand out the window to signal to the workers that we needed to once again get under the truck to see what was wrong with the axel.

The workers came back to the truck. They tightened and banged a few things that we couldn’t see and we were once again on our way. We drove for about 15 minutes further before once again stopping to adjust something with the axel. We drove again for about 15 minutes before reaching a very steep hill, with loosely packed dirt beneath us. Emilio stopped the truck. He lifted the front hood and we poured cool water over the radiator, which was overheating. The water steamed on the hot engine and the sun was high in the sky. We were surrounded again by the beautiful pine clusters with agaves scattered about the floor of the forest.

The truck that belonged to Emilio’s father, with axel issues on the side of the road. We enjoyed our time resting with the beautiful landscape all around.

Emilio pouring water on the overheating radiator as we attempted to climb a hill in the truck. Again, we were happy to wait and enjoy our time away from the hustle.

It was at this moment that I realized how much this truck truly meant to Emilio. This was the 4th time we’d stopped to fix something. The trip that was supposed to take us 1.5 hrs had already taken almost 3 hrs and we weren’t there yet. But this truck belonged to his father, before he passed away. It was a remnant from Emilio’s past, something that he was trying to keep alive and active and relevant. He has a newer truck. We saw it, and we presumably could have taken that truck and avoided these issues with the axel and radiator. Instead, Emilio chose to keep his father’s truck in action, to keep that past alive and honor it. He intentionally chose to take his father’s truck, just like he intentionally chooses to keep the history and tradition of his family’s mezcal production alive each day.

There are always shortcuts out there. There is always an easier route or some new technology that will quicken some process or make it more efficient. But what do we lose when we adopt and implement those shortcuts? What happens when we choose to make mezcal in a cheaper or more industrial way? What if we choose to ignore the community and the land that surrounds us? What do we lose when we let the old truck lie fallow? Will it ever start again? Emilio doesn’t take the easier path. He’s chosen a path that honors his family, his community, and all of the traditions that he keeps alive today. It’s the higher road, and an honorable road, that makes him who he is today.

The Agave Fields of El Limon

Just before arriving at the El Limon agave fields, Emilio pulled the truck to the side of the road. I initially thought it was another issue with the truck but he stepped out of the truck and pointed off in the distance. By this time, we were on the opposite side of the pine forest canyon and he told us that we could see the roof of his vinata from there. He said that he liked to stop here because the vinata looked so small from this location. It was kind of a Carl Sagan, Pale Blue Dot type moment. Looking over at the tiny vinata on the massive mountainside before us. The landscape was immense and the vinata was so small. It was a truly humbling view and moment in time, a sign of the depth at which Emilio engages with his surroundings.

A view from across the canyon, looking back at Emilio’s vinata, his pale blue dot. Can you see it on the distant hillside?

We finally arrived at the agave fields at El Limon and they were spectacular. The views expanded in all directions. All of the agave cultivated at El Limon are certified Bat Friendly, meaning that (among other things) he allows at least 5% of the plants to go to seed, creating greater biodiversity within the field. Emilio also told us about agave that reach maturity via la jarilla. This is a term used in Michoacán for the ~5% of agaves that never grow a quiote at the time of maturity. Instead, the pencas close up in the center as if the agave is making a giant point toward the sky. This is a sign that the agave is ready to be harvested despite the lack of quiote. It’s not common and Emilio wants to make an entire batch of mezcal with la jarilla agaves but that hasn’t happened yet.

Emilio’s agave fields at El Limon. The agaves here are Bat Friendly.

Back at the Vinata

We returned to the vinata after a wild journey back. There were no more truck issues, but we stopped at the tienda of Emilio’s uncle to taste some of his mezcal and have a beer. Back at the vinata, Doña Delia had cooked a massive meal for us while we were away. She has a full open-air kitchen at the vinata and she loves to talk about the fresh ingredients and spices she uses in all of her food. Emilio showed us his above-ground storage room, as well as his underground mezcal cave. The cave is a room beneath the vinata where he stores his most cherished mezcals. Above the doorframe to the cave rests a memorial to Emilio’s father. We tasted several mezcals from the cave, which were all incredible. It’s clear that he is really keeping his best in deep, dark storage for the time being.

The above-ground storage facility. This room was full of mezcal batches from various years.

The older Don Mateo labels on the left, and the new labels on the right. You may still see either in stores/bars.

Emilio’s cave beneath the vinata, dedicated to his late father. See the plaque above the doorway.

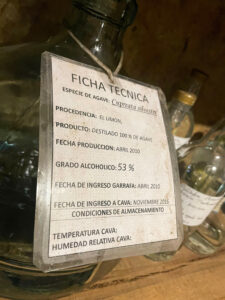

The oldest batch in Emilio’s cave. This was a fantastic wild cupreata from the fields at El Limon, produced in April of 2010.

A view from within Emilio’s cave, filled with mezcal that has been aging for years. Only his most special batches make it down into the cave.

Mezcal aging in Emilio’s cave. From left to right, these batches are from May 2012, April 2010, and March 2013.

I purchased a bottle of Don Mateo Pechuga at the vinata and Doña Delia insisted on writing a message on the bottle: Con mucho carriño para Jonny de Delia (with love to Jonny from Delia). Doña Delia is the most hospitable and warming person I have ever met. I don’t say that lightly. She is an incredible human being and an absolute miracle on this earth, bringing warmth to everyone she encounters.

Doña Delia insisted on signing the bottle of pechuga that we purchased at the vinata. Again, this is her pechuga recipe and she takes great pride in it.

The signed bottle of pechuga from Doña Delia.

We left the vinata in the dark of night, and headed back to Morelia. We’d been there all day and were exhausted yet elated by the experience. We’ve met a lot of great people through this website and mezcal project, yet Emilio and Doña Delia genuinely stand tall amongst the mezcal giants that we’ve met before them. They understand that what they’re doing is not only keeping a group of concentrated traditions alive, but that they’re projecting this out to a wider audience. Most of the time when we visit similar mezcal titans, they are at the tail end of their production careers. That’s not the case with Don Mateo. Emilio is still very young and his mother is more full of life than anyone I’ve ever met. With how much they’ve accomplished already, and over 400 years of mezcal production in their past, it seems that things are really just beginning for Mezcal Don Mateo, which is very exciting.