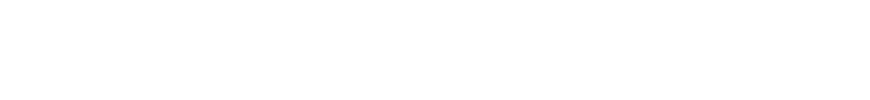

After the Mexican Revolution, a new constitution was drafted in 1917, which included the empowerment of the government to expropriate privately held resources, including land. Sweeping land reform followed and continued to evolve for the years following. By 1934, Lázaro Cárdenas became president and he introduced policies that allowed for rural farmers to petition the government to exercise eminent domain against wealthy land owners in their area. The result of this petition would be the seizure of a small portion of the land from the wealthy land owners, and the establishment of communal land, which became known as an ejido. Power to the people!

By definition, an ejido is an area of communal land used for agriculture in which community members have rights to use the land rather than ownership rights to land, which in Mexico is held by the Mexican state. The typical process for the establishment of an ejido followed these general steps:

- Farmers who leased farmland from wealthy landlords would petition the federal government for the creation of an ejido in their general area.

- The federal government would consult with the landlord.

- The land would be expropriated from the landlords if the government approved the ejido.

- An ejido would be established and the original petitioners would be designated as ejidatarios with specific cultivation and usage rights.

Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas, who introduced the ejido system to Mexico, on the cover of Time Magazine on August 29, 1938.

Ejidatarios did not actually own the land but were allowed to use their allotted parcels indefinitely as long as they did not fail to use the land for more than two consecutive years. They could also pass their ejido rights on to their children. That lineage over the ejido land is important, as it provided the offspring of the Ejidatarios with the opportunity to access these community resources.

New ejidos continued to be created between 1934 and 1991 when President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, as part of Mexico’s preparations for the North American Free Trade Agreement, ended the establishment of new ejidos and allowed existing ejidos to be sold to private owners. Some ejidos were sold to private buyers, but many are still in existence and play an important role in small communities across Mexico. These current ejidos are still governed by ejidatarios and their surviving family.

So what do ejidos have to do with mezcal?

Many mezcaleros live and produce mezcal in very rural areas of Mexico. Historically, many of the families that produce some of our favorite spirits have existed for generations as subsistence farmers. Some of those families own land for themselves, and they use that land for livestock and the cultivation of crops, including the agave they use in their mezcal. Unfortunately, not all mezcalero families own land. Some need to rent land from nearby landowners, some purchase agave from other agave cultivators in the region, and some are fortunate to be the sons and daughters (or grandsons and granddaughters, etc…) of an ejidatario. And that’s where Miguel Ortiz Villagomez comes in.

Maguey Melate

We were first introduced to Miguel Ortiz Villagomez via the Maguey Melate Mezcalero of the Month Club. For those who don’t know, Maguey Melate is a monthly subscription service that sends you two 375ml bottles of mezcal delivered directly to your door. This is a true palenque-to-table service, and it encompasses a whole lot more than just the juice.

It’s a full experience with mezcalero interviews, personal histories, and drone footage of palenques/vinatas/tabernas. It’s as close to visiting a mezcalero as you can get without actually going out and travelling to see them yourself. They feature agave spirits producers from all over Mexico, so it’s a great opportunity to taste different agaves, from different regions, using different production methods. I’ve been a monthly subscriber since the project launched in early 2019. Miguel Ortiz Villagomez was Mezcalero of the Month for April 2022, and the club featured his Agave inaequidens expression.

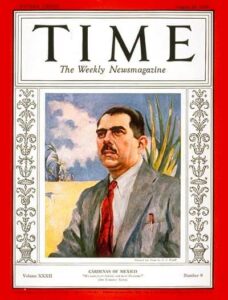

Maestro Mezcalero Miguel Ortiz Villagomez.

The Maguey Melate agave spirit of the month from Miguel Ortiz Villagomez in April 2022.

Ióntki Anapu

Fast forward to Spring 2023, we were planning a trip to Michoacán and a visit to Miguel Ortiz Villagomez was high on our list. I reached out to Dalton, the founder of Maguey Melate, and he got me in touch with Emiliano Raya Aguiar. Emiliano is a PhD professor of 20th-century Mexican history in Morelia, the capital city of Michoacán. His specialization focuses on the history and relationship between the indigenous tribes and the European descendants in the central Mexico region.

In partnership with Miguel Ortiz Villagomez, Emiliano runs the Juchari Icheriicha Cooperative, which includes their brand Ióntki Anapu, which means “very old,” in recognition of the ancient drink. Both the name of the collective and the mezcal brand are in the native Purépecha language of this region. Emiliano told Melate; “The philosophy of the Cooperative is to rescue the historical memory of popular Mexican traditions. We believe that one way to do it is through mezcal, a drink that synthesizes the cultural essence of the Mexican people as it is the result of cultural miscegenation.”

Ióntki Anapu bottles as they are sold in Mexico.

Visiting Cañada del Agua

Emiliano called me early in the morning to say that he’d meet us out at Miguel’s vinata later in the day. Instead, Miguel’s cousin picked us up in Morelia, and we made our way out to Cañada del Agua. It’s about a 2.5 hour drive through the rich and green countryside, up into the hills. As we entered the tiny town, we stopped for two cattle ranchers, allowing them to cross the road with their cattle. We’d find out a few days later that these two ranchers were actually were the mezcalero brothers Jorge and Miguel Salinas. “We saw you here in town earlier this week” they’d tell us when we visited them a few days later. The town is no more than a collection of a handful of houses. They don’t get many visitors.

Miguel’s house is at the corner of what seems to be the only intersection in town. In addition to making mezcal in his small backyard, he also runs a small country store type shop in a front room of his house, which opens up onto the main road. The mezcal production area behind the house is very limited, with just a single still and two stone fermentation tanks. There’s a small stream that runs through the production area, but Miguel does not use water from it due to an agricultural operation that is further upstream. He says they sometimes use chemical fertilizers in their fields and he doesn’t want those chemicals in the water he uses for his mezcal production. Instead, he trucks in massive water containers from a nearby town.

The vinata behind Miguel’s house. The agave is cooked down the road and then brought here for fermentation and distillation.

The single Filipino still that Miguel uses to make his mezcal.

The production area was so small that we didn’t spend much time there. Instead, we jumped into Miguel’s truck. He wanted to show us his agave fields, and he stopped at a small store on the outskirts of town to pick up some Corona tall boys for everyone to drink while we walked through his fields. The landscape was an incredible mix of ranchland and vast agricultural operations. His agave fields were a mix of the two: rows of planted agave with seasonal grasses grown in between the rows for cattle to eat, digest, and defecate while they stayed in his field. This provides fertilizer to help the agaves in their growth, while also making the most of the space and it’s possible uses.

An agave field just down the road from Miguel’s house.

The largest of the agave fields that we visited with Miguel. This also was some of his most mature agave.

Some of his agave fields are upwards of a 20 minute drive from his house, and we walked through agave fields for what seemed like most of the morning, enjoying the cool weather and the tranquility of the countryside. Our final stop on the way back to his house was at a small plot of land where Miguel has two pit ovens for roasting his agave. With no room at his house for cooking the agave, this is where he first takes the raw harvested agave. Once cooked and cooled, he takes the agave further up the mountain to his house, where he mills, ferments, and distills his mezcal. It’s an additional complication to an already complex process, but he doesn’t seem to mind. Given the high altitude and relatively cold temperatures of the town, Miguel also has to add pulque to his fermenting agave. He sometimes adds up to 20 liters of pulque to jumpstart the yeast-sugar interactions in the agaves.

An oven that Miguel uses to cook his agave. This is down the road from his house.

El Ejido de Cañada del Agua

We arrived back at Miguel’s house, exhausted from hiking through his agave fields all morning. Emiliano had just arrived and was full of energy. “Let’s get some mezcal and go up to see the ejido,” he told us excitedly. Not really knowing what this meant at the time, we agreed and jumped back into Miguel’s truck. We again stopped by the small store on the outskirts of town to buy more Corona, and then we drove straight up the mountain.

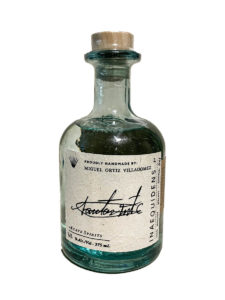

Densely wooded slopes on either side of the mountain road loomed over us as the truck climbed higher above the valley. We eventually came to a small clearing on a steep slope where several agaves had recently sprouted quiotes. Miguel stopped the truck and Emiliano grabbed several coa de jima from the back bed.

“That’s the one,” Emiliano said, pointing up the hill. “That’s the one we’re going to harvest today.” We grabbed the coas and Miguel showed us the proper technique. To put it plainly, harvesting agave is really tough. There’s probably no better way to truly understand the labor involved in mezcal production. What Miguel told us would have taken him 5 minutes to harvest, took us upwards of 30 minutes, just to trim down the pencas and expose the piña. In the end, my hands were full of popped blisters, my back was aching, and my belly craved any bit of sustenance and additional energy to burn.

Miguel showing our friend Chris how to properly remove the pencas.

Miguel finishing the smoothing of an agave.

We rested in the long grass for a few moments and looked out at the valley far below. Miguel explained that this ejido had been passed down from his father. He didn’t know the exact date of the establishment of this ejido, but he said that his father had inherited it from his father (Miguel’s grandfather), so it’s at least a few generations old. The whole piece of land is only 200-300 hectares (494-741 acres), which Miguel saw as a small piece of land. The community still uses the property frequently for farming and animal husbandry. It’s a critical resource for the community, and it’s crucial to Miguel’s mezcal production as he’s not able to harvest enough agave from his fields to meet the demand for his mezcal.

Miguel and Emiliano at the top of the mountain in the ejido.

After awhile, Miguel took us further up the mountain, into the ejido. The views of the mountains and landscape below were breathtaking. We looked out over the ejido, a holdover now from the great Mexican land reform that started with the revolution over one hundred years ago. We sipped Miguel’s mezcal, chased by cold Coronas and small snacks from the town store.

Miguel and Emiliano explained that the Ióntki Anapu project is really just getting started. As of the writing of this blog post, the best way to get Miguel’s mezcal in the US is through the batches imported through Maguey Melate on their online store. It’s not always in stock there, but it’s worth a look from time to time as they’ve imported a few different batches through Melate. If you’re in Mexico, you can find the Ióntki Anapu brand in Morelia, Mexico City, and more places soon.